The Ontario towns of Leamington and Kingsville have some of the highest rates of coronavirus infection in Canada, with large outbreaks on farms and at greenhouses. The province has started testing migrant workers, but these new measures overlook undocumented workers.

The house where the undocumented workers live isn’t hard to find.

Located just 100 metres from one of Leamington, Ontario’s main intersections, the sprawling structure has clearly seen better days. The paint is peeling, shingles are curling, and some of its filthy windows are cracked.

Yet it is home for nearly 20 foreign farm labourers — most of them lacking the proper permits to work in Canada. Men who are now trying to balance concerns about COVID-19 with fears that the act of getting tested might get them deported.

“If I get sick, there is no solution,” says one resident. “Because I don’t have money.”

The 43-year-old came to Canada from Guatemala a year ago under a government program. His permit has since lapsed, but he continues to work, moving from farm to farm as a temporary hired hand, and sending his modest wages back home to support his wife and 11 children. He asked not to be named because of his immigration status.

And despite the outbreak in Southwestern Ontario that has now sickened close to 1,000 migrant farm workers — most in Leamington and neighbouring Kingsville in Windsor-Essex County — and killed three of them, the man says he has no plans to get tested for the novel coronavirus.

“I don’t show any symptoms. I don’t know anyone who has it, and I feel there’s no need to at the moment,” he says. “I don’t see it, so it doesn’t exist to me.”

Provincial ‘action plan’

Agriculture is big business in Windsor-Essex, with more than 175 farms, greenhouses and wineries contracting some 8,000 official migrant workers to help raise and harvest the crops every year.

So as coronavirus cases began to spike among workers, Ontario Premier Doug Ford unveiled a three-point “action plan” last week, dispatching mobile testing units to farms, promising benefits and supports for ill workers who are put in quarantine, and altering rules to allow farmers to keep asymptomatic labourers on the job.

WATCH | Trudeau on the temporary foreign workers who died from COVID-19:

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau says “rules weren’t followed” in the cases of temporary foreign workers who were infected with and died from COVID-19. 0:45

But none of his measures target undocumented workers, who are unlikely to present themselves for testing, and don’t qualify for free provincial health care, let alone any sort of government employment assistance.

It’s a gap that could make it more difficult to bring the farm outbreak under control, given the large number of so-called paperless labourers in the area, and help keep Leamington and neighbouring Kingsville the last two places in the province stuck at Stage 1 of the pandemic lockdown.

Santiago Escobar is a national representative with the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, and a co-ordinator of the Agricultural Workers Alliance. He spent two years working out of a satellite office on Leamington’s main street, and says the local population of undocumented workers was much larger than the province or Ottawa liked to let on — as many as 2,000 workers, by his and other advocates’ estimates. A big number that Leamington Mayor Hilda MacDonald has also been citing.

“I think is it’s common knowledge that most of the workers that are hired through a temp work agency are undocumented,” says Escobar. “And due to their precarious status, unscrupulous employers and temporary work agencies are taking advantage of these workers.”

‘No masks, no gloves’

Rogelio Muñoz Santos, a 24-year-old from Chiapas, Mexico, arrived in Canada on a tourist visa in February. His family have told Mexican media outlets that he found a Spanish-language post on a Toronto Facebook page offering farm jobs paying $13 an hour — $1 an hour less than Ontario’s minimum wage — for a 70-hour week. He arrived in Leamington in early April.

He ended up living in a local motel, arranged by his recruiter, with four men sharing two beds and a bathroom, at a cost of $600 each per month, deducted from their pay.

His co-worker, who asked to be identified only as “Juan” because of his own undocumented status, recently told CBC’s French-language service Radio-Canada about how they both fell ill in early May as a flu-like illness swept through the farm where they were working.

“I didn’t want to work because I was already feeling sick. Everyone was getting ill, but they sent us to work all the same,” Juan said, noting that they travelled in vehicles containing as many as 20 people at a time. And no one took any measures to protect them from coronavirus spread. “No masks, no gloves, or goggles or information.”

The pair didn’t have a relationship with the farmer, only with the temp agency recruiter — a Spanish-speaking Canadian who paid them in cash. And when they fell sick with the novel coronavirus, isolating themselves at the motel, a public health nurse would call to check up, but no one brought them food or supplies.

“They abandoned me,” Juan said. “Same with Rogelio. They did nothing for me or for him.”

Muñoz Santos was admitted to Erie Shores Hospital in Leamington on June 1 with breathing difficulties, and transferred to an ICU in Windsor the next day. He died in hospital on June 5. It took more than three weeks for his body to be returned to his family in Mexico. He was finally laid to rest on June 27.

Barriers to fighting farm outbreaks

Dr. Ross Moncur, the chief of staff and interim CEO at Erie Shores Hospital, says there have been a series of barriers to overcome as health officials try to fight the farm outbreaks. Many workers have been reluctant to get tested for fear of losing weeks of income should the results come back positive. And some farmers have resisted, as well, concerned about the potential fallout during their busiest time of year. “What happens to their workforce?” asks Moncur. “Does it mean that they literally have crops rotting in the fields for the next few months?”

But undocumented workers are proving the hardest to reach.

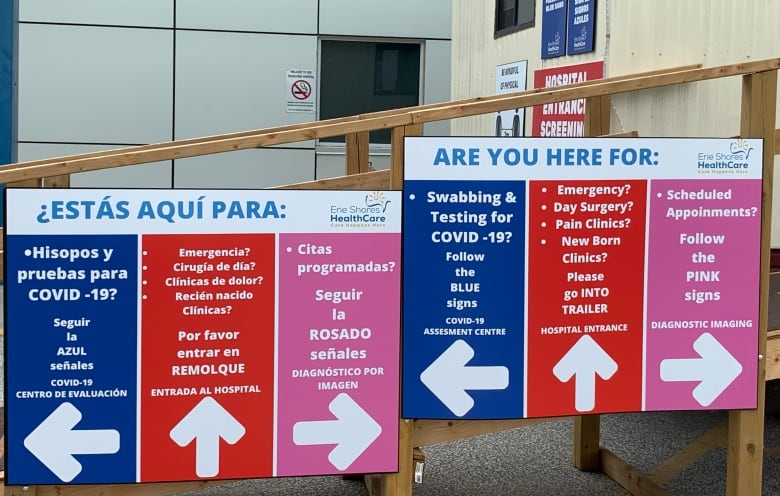

“The biggest impediment there is that they don’t have [provincial health insurance] coverage, and so their assumption is that this type of testing is not available to them,” Moncur said, noting that his hospital will treat anyone who needs care, regardless of their immigration status.

That message, however, doesn’t seem to be getting through. CBC News spoke to a number of undocumented workers in Leamington. None of them had been tested. And few seemed aware that the local hospital was providing free COVID screening just a few blocks away from where they live and shop, complete with Spanish signage and interpreters.

Some were taking a fatalistic approach to COVID-19. One worker, a 39-year-old from Mexico who entered Canada on a tourist visa 10 months ago, says he’s leaving things up to a higher power should he fall ill.

“First, I would pray to God. If he sends me, allows me to go to hospital, I’ll go to the hospital,” he says. “But we are all going to die one day. We never know how. So it might be here or it might be in Oaxaca. We just don’t know.”

Asked specifically about their efforts to reach undocumented workers, Ontario Health, the agency overseeing the testing told CBC News that it is working with “key stakeholders” in the agricultural industry “to understand the full breadth of needs” and “other factors relating to the temporary worker experience in Ontario.” The agency stressed that testing is available to all workers, regardless of immigration status, but remains voluntary.

Justine Taylor, the science and government relations manager for the Ontario Greenhouse Vegetable Growers, says the Leamington-based organization has been encouraging its members to have all farm labour tested for coronavirus, regardless of how they have been hired.

Officially, the group doesn’t support the use of undocumented workers, although Taylor acknowledges that it is a “very complicated” issue for farmers, who often struggle to find enough hired help during their busiest periods.

“There is a need there,” Taylor said, adding that her association wants to work with governments to close the undocumented “gap” and “ensure that all workers are protected.” One path, she says, might be to follow British Columbia’s lead and create a provincial registry of recruiters and make farmers hire only from the accredited firms.

All such measures, however, will address the future, not the current crisis.

Erie Shores’ Moncur says there is a sense of a missed opportunity in Windsor-Essex, that these farm outbreaks — and deaths — were all too foreseeable.

From the very beginning, local health officials understood that agricultural workers were a “high-risk population,” he says, due to their living and working conditions. But the system was consumed with fighting COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, where more than 300 outbreaks have killed some 1,600 residents.

“We may have had a false reassurance that because they were relatively young and relatively healthy, that agrifood workers would be OK,” Moncur said. “That theory was certainly tested.”

And with hundreds of new cases this past week — 175 of them on a single farm — the region’s battle against COVID-19 is only beginning.

With files from Madeline McNair, Laura Clementson, Thilelli Chouikrat and Susana Gómez Báez