Prime Minister Scott Morrison wants Australians to get back to work, after several weeks of strict coronavirus restrictions wreaked havoc on the economy.

With the curve well and truly flattened, measures are slowly being relaxed and the Government is keen for a cautious return to business as usual.

But new research has painted a stark picture of how quickly COVID-19 can tear through a workplace and create serious clusters – with wide-reaching ramifications.

The study, published today in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s medical journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, examined an outbreak in Korea in early May.

And it shows just how quickly a serious cluster can develop.

RELATED: Follow the latest coronavirus updates

On March 8, health authorities were notified of a confirmed case of coronavirus in a call centre worker that was feared to be from a cluster.

The next day, an emergency response team was formed and the 19-storey building in one of Seoul’s busiest commercial precincts was shut down.

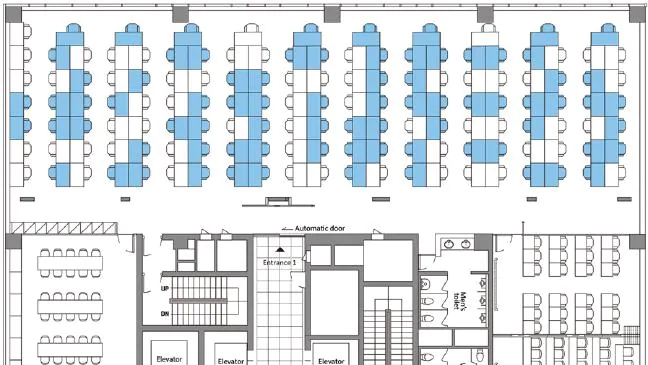

The mixed-use building comprised commercial offices and residential apartments, with the call centre housed on four floors employing a total of 911 people.

Health workers tested 1143 people who were in the building or had visited and detected a total of 97 cases of COVID-19.

All but three of those people worked on the 11th floor of the call centre business, which had 216 employees, translating to an infection attack rate of 43.5 per cent.

“Most of the case-patients on the 11th floor were on the same side of the building,” the study found.

That shows how sustained close contact indoors can see coronavirus spread rapidly.

Subsequent contract tracing and follow-up determined that there was a secondary infection rate in households of 16.2 per cent – that is, the number of infected workers passed it on to loved ones in their homes.

“COVID-19 had occurred in 34 household members who had contact with symptomatic case-patients,” the study said.

Health officials moved swiftly when the outbreak was detected – and their approach could be a guide for other countries who are slowly returning to business as usual.

The researchers attempted to track the source of the outbreak in the workplace and their findings are cause for concern.

“The first case-patient with symptom onset, who worked in an office on the 10th floor and reportedly never went to 11th floor, had onset of symptoms on February 22,” they found.

“The second case-patient with symptom onset, who worked at the call centre on the 11th floor, had onset of symptoms on February 25.”

In the 12 days that follow, that one infected person spread coronavirus to 93 other people on their floor.

How the first case on a separate floor, in a person who did not visit the 11th floor, is unclear.

However, the study noted that: “Residents and employees in (the) building had frequent contact in the lobby or elevators.”

RELATED: When will lockdowns ease in my state?

Despite that casual contact, the study identified “alarmingly” that coronavirus can be “exceptionally contagious” in crowded office settings.

“The magnitude of the outbreak illustrates how a high-density work environment can become a high-risk site for the spread of COVID-19 and potentially a source of further transmission.

“Despite considerable interaction between workers on different floors of (the) building in the elevators and lobby, spread of COVID-19 was limited almost exclusively to the 11th floor, which indicates that the duration of interaction or contact was likely the main facilitator for further spreading of (coronavirus).”

Analysis of this outbreak illustrates the “threat” posed by coronavirus in sparking large outbreaks among people in office workplace environments.

“Targeted preventive strategies might help mitigate the risk for (COVID-19) infection in these vulnerable groups,” the study said.

“Extensive contact tracing, testing all contacts, and early quarantine blocked further transmission and might be effective for containing rapid outbreaks in crowded work settings.”

How health authorities dealt with this particular case could also be a model for other countries – including Australia – who are slowly returning to working onsite.

“Confirmed case-patients were isolated, and negative case-patients were mandated to stay quarantined for 14 days,” the study said.

“We followed and retested all test-negative case-patients until the end of quarantine. We also investigated, tested and monitored household contacts of all confirmed case-patients for 14 days after discovery, regardless of symptoms.”

Read More