Monkey Business (Part 1)

There is an ongoing urban war on the Cape Peninsula — humans versus baboons

For as long as there have been humans and baboons, there have been conflicts over resources. The idea that the violent separation of baboons and their human neighbours is the only option is a profoundly political one that must be re-thought, especially in this era when urban societies have expanded and animal habitats are under threat.

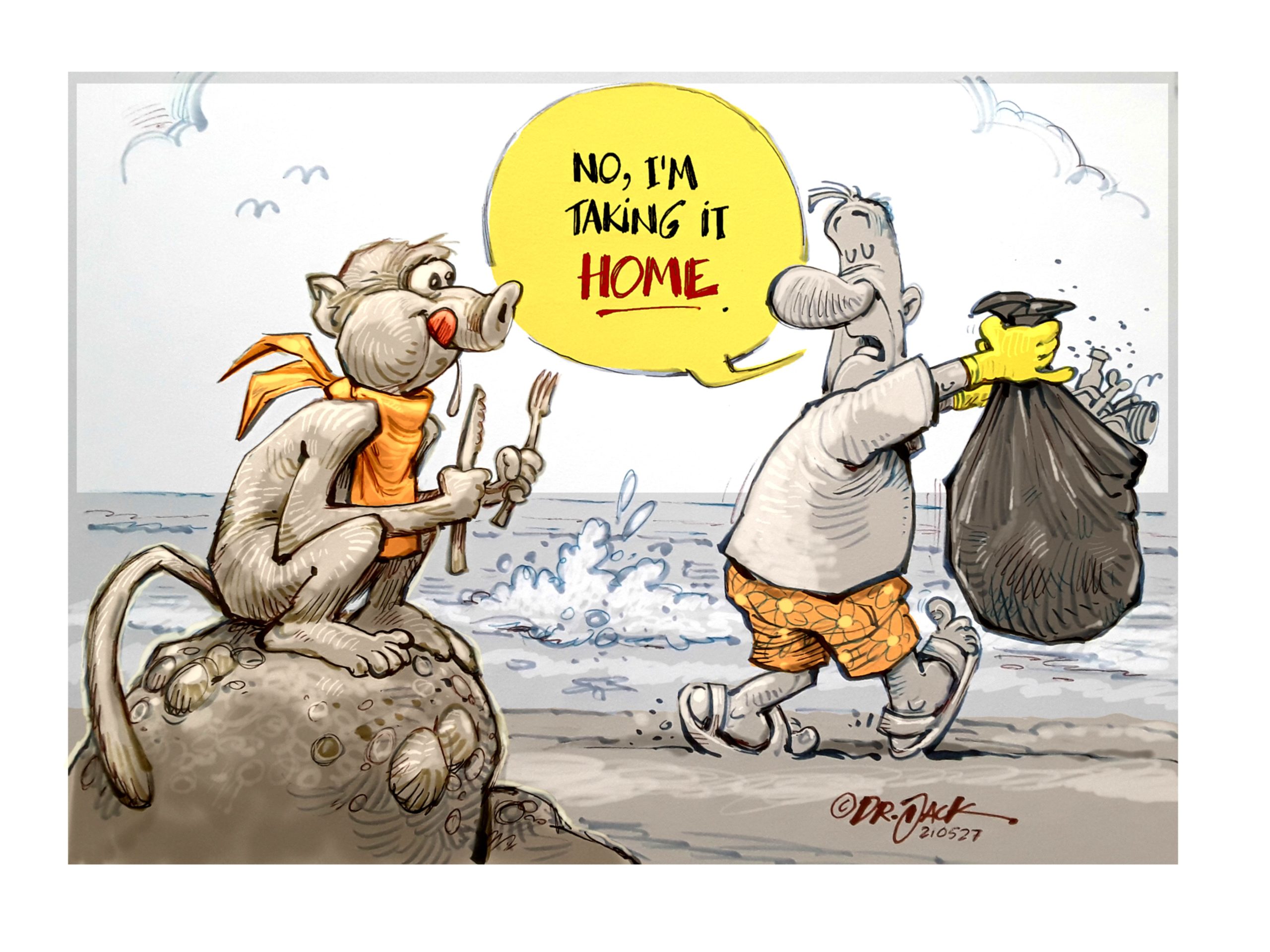

Baboons on the Cape Peninsula are seen as “raiders”, “robbers”, “gangs”. They are criminalised and forced to the edges of their own habitat. If they “trespass” they are shot at with paintball markers.

Need for a Solution

Prof Lesley Green, an anthropologist and director of environmental humanities at the University of Cape Town, notes that “baboons are trying to live on the edge and we need to find a solution to live with them. What does it mean to be a neighbour of baboons? You have to manage the relationship.

“Would any of the officials paintball their dogs or their neighbours? Of course not! Humans and baboons have always been uneasy neighbours, but building relations of care for good neighbourliness in baboon neighbourhoods is both possible and preferable to violent policing.

“How did we get to this situation where we agree that life on the urban edges must be characterised by the violent separation of people and animals?” she asks.

“Controlling a baboon’s movement through pain is not necessary if what is on the other side is not attractive. Paintballing and culling of baboons are absurd and unfair, without attention to the specific roles people play in each neighbourhood.

“Why is there not a single social scientist on the baboon management team, to advise on baboon-human relations in different neighbourhoods? Each range of Cape Town’s various baboon troops extends to areas with different daily or weekly rhythms; different patterns of food growing or storage and different kinds of food waste and waste management concerns.

“Every neighbourhood has a different human presence in its streets, and if the relationship of baboons and people is to be better governed, each should be understood via its specific patterns of life that create different invitations and opportunities for baboons.

“One can’t govern with a one-size-fits-all approach that draws property lines enforced with paintballing: that is simply not responsive governance.

Can People & Baboons Be Better Neighbours?

“At the end of the day, you are asking people and baboons to be better neighbours. But the current policy of the City of Cape Town is fostering a relationship of conflict and violent policing, instead of building responsible neighbourliness,” said Green.

For as long as there have been humans and baboons, there have been conflicts over resources. The idea that the violent separation of baboons and human neighbours is the only option is a profoundly political one that must be re-thought, especially in this era when urban societies have expanded and animal habitats are under threat.

“Can humans and animals be good neighbours? Yes, of course they can. But like any relationship it requires both parties to be responsible, not only one. Society and nature are not separate; they never have been and never will be. But as long as that idea is in place, it will provide a rationale for the violent policing of that imagined boundary,” argues Green.

Not only is social science absent in baboon management, notes Green, but the approach to primatology is limited.

“Why has only one approach to primatology been allowed to have a voice in the debate — the approach that presumes power and violence to be central to baboon life? The split between feminist and patriarchal approaches to primatology has been central in global debates for decades, but it is totally absent in Cape Town.

“The advising primatologists present their approach as ‘the voice of science’, but their approach is rooted in a masculinist patriarchal approach to baboon behaviour that is deeply contested in scientific contexts elsewhere.”

Baboons Are Being Killed

Dr Elisa Galgut, a trustee of Baboon Matters, said she has questions for the authorities:

“If the current management tools are said by the authorities to be working, why are baboons still being killed? The defence of aggressive tools such as paintballing is that ‘it’s better to use paintballs than to have baboons killed’. But baboons are still being killed — so will the city admit that current tools are not working?

“Why is there still a waste management problem on the peninsula? If the city took the welfare of the baboons seriously, one would think that all efforts to manage waste effectively would be the first thing the authorities would do.

“It is of great concern to note that these aversive techniques are being applied even though no official ethics review has been done. Nor, as far as I know, is there any consultation with an ethicist regarding baboon management. If a university, for example, wanted to use harmful and aggressive tactics in animal research, the protocol would have to be subject to ethical review. It’s not clear why conservation management tools are not required to undergo similar ethical review.

“Moreover, the authorities appeal to behavioural psychology in defence of these aversive techniques, but as far as I know, there is no behavioural psychologist on the committees that oversee the protocols,” Galgut said.

Aggressive Tactics

“The most concerning aspect of baboon management in the Cape is the use of aggressive tactics such as paintballs, and the killing of male baboons — over 70 baboons have been killed under the management strategy, which clearly indicates that the management is not working. The refusal of the authorities to manage the waste is also of extreme concern,” Galgut said.

The City of Cape Town was asked why it still supports the use of paintball markers when the SPCA withdrew its support for it. Marian Nieuwoudt, the MEC for Spatial Planning and Environment, said: “This has recently been changed and the Cape of Good Hope SPCA does support the interim use until the guidelines/protocols are reviewed.”

At the time this question was asked, the Standard Operating Procedures for the use of paintball markers were updated and the SPCA did not support it.

Jaco Pieterse, chief inspector of the Cape of Good Hope SPCA said: “The SPCA does not support, promote or endorse the use of paintball markers; however we cannot ban or stop their use, provided that it is used in a humane manner. The SPCA however believes the indiscriminate use of paintball guns fired at point-blank range at animals causes unnecessary suffering and therefore constitutes a criminal and prosecutable offence in terms of the Animals Protection Act 71 of 1962.”

Baboons are often injured and illegally shot and harmed by residents, and then it becomes the responsibility of the SPCA.

The budget to pay NCC Environmental Services to run the Urban Baboon Management Plan is “between R12-million and R14-million, depending on increases and contingencies. With HWC, it was slightly more,” she said.

“The injured baboons (as a result of human-induced conflict) are not the mandate of the city and, in addition, the city does not have the budget or the resources to intervene. The city alerts the SPCA and, on occasion, CapeNature, and assists where possible,” she said.

Pieterse said the city has “not offered any financial contributions towards the treatment of any baboons. The SPCA is absorbing all the expenses. It costs the SPCA just over R5,000 to dart a single baboon, as we have to use a private veterinarian with a dart gun. Then there is also the additional cost of treatment that also falls on us.

“Responsibility needs to be accepted for injured baboons and this must not fall on to the SPCA. Currently, no one intervenes with injured baboons besides the SPCA, and the expenses we are incurring are astronomic.”

The rules also state that any baboon that is injured and treated only has five days to recover or improve before it is euthanised. The five days seems rather arbitrary, said Galgut.

Taryn Blyth, an animal behaviourist, said that by applying aversive techniques (paintball guns and bear bangers) that are associated with people rather than the urban area, we potentially risk creating aggression in the baboons, which, instead of seeing people as “neutral”, could associate people with something threatening, which could cause defensive aggression.

By creating a negative association with people, but still providing rich food sources through unsecured waste and fruit trees, we may be creating “approach-avoidance conflict”.

The baboons have both negative and positive associations around people, in as much as people do “scary stuff” to them, but where people are also a great food source.

Punishment + Reward = Conflicted Baboons

Creating both associations of punishment and reward with the same stimulus (being around people) could cause the baboons to become extremely conflicted, and be caught between wanting to approach to get food, but at the same time wanting to avoid danger. This emotional conflict tends to lead to high levels of stress and unpredictable behaviour, such as aggression, she said.

According to the standard operating procedures, only adult baboons may be targeted with paintball markers. No adult females carrying infants may be shot at; the field guide working for NCC may only target adult baboons that are within a safe distance from juvenile and infant baboons, but within 20m of the guide.

What the World Wildlife Fund Says

Living with wildlife, as humans have for ages, is expressed in a recent 130-page document with the World Wildlife Fund.

In A Future for All: The need for human-wildlife coexistence, the authors write: “Around the world, human-wildlife conflict (HWC) challenges people and wildlife, leading to a decrease in people’s tolerance for conservation efforts and contributing to multiple factors that drive species to extinction.

“HWC is a significant threat to conservation, livelihoods and myriad other concerns and should be addressed at a scale equal to its importance. By allocating adequate resources and forming wide-ranging partnerships, we can move towards long-term coexistence that benefits both people and wildlife.

“We are convinced that if we adapt, replicate and scale up those successful efforts in a more concerted manner globally while considering local contexts and needs, we may well be able to achieve some level of human-wildlife coexistence. The time has come for stakeholders to step back and rethink how they can reduce and manage conflict between people and wildlife and foster coexistence for the benefit of both wildlife and people.”

As implemented in Cape Town, however, the human-wildlife conflict paradigm holds only baboons to account, said Jenni Trethowan, from Baboon Matters Trust: “Over the years, baboons have been paintballed in sleep sites, on waking, whilst foraging, even after having just given birth. They have little respite and are kept in areas that are easy to manage, so seasonal movement and wide-ranging foraging is effectively curtailed — possibly driving the ongoing need to grab high reward human foods.” DM/OBP

This is part one of a three-part series into the interconnectedness of communities living on the urban fringe and baboons and on how, if at all, the two can co-exist. In Part Two, we ask: Who is responsible for the management of the baboons on the Cape Peninsula?

You can read Part 3 here.

This article first appeared on Daily Maverick and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

The Argus Report Read about it!

The Argus Report Read about it!

2 comments

Pingback: Baboon Matters - The Argus Report

Pingback: Baboon Management Plan - The Argus Report