By JANE DUNCAN

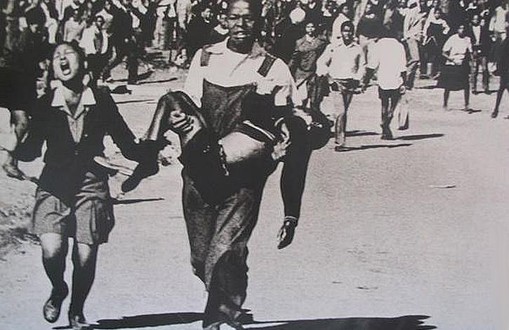

On 21 March 1960, the apartheid police opened fire on a crowd of protestors in Sharpeville, killing 69 people. Five decades on, post-apartheid South Africa remembers these events annually, on Human Rights Day. The government has attempted to depoliticize the event, shifting the day from one that is associated with the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) to one that South Africans generally commemorate, irrespective of their political persuasions.

Yet the annual commemoration of this day did not stop a post-apartheid massacre from taking place in Marikana. It did not stop the ejection of the Economic Freedom Fighters from Parliament en masse even before they had become disruptive.

It did not stop the State Security Ministry from insulting the public’s intelligence with a nonsense excuse for why cellphone signals were jammed in the National Assembly chamber. It has not stopped the State Security Agency (SSA) from announcing that it intends to investigate, on the smell of an oilrag, the claims that several public and political figures are Central Intelligence Agency spies.

It did not stop the indiscriminate arrests of women in Chaneng in the North-West on Human Rights Day in 2013. Predictably, charges against them of illegal gathering and public violence were withdrawn for lack of evidence over a year, and many court appearances, later. It has not stopped this all too familiar cycle from unfolding in Thembelihle in the past two weeks.

Disrespect for Basic Human Rights

The security cluster’s stunning disrespect for basic human rights gives credence to arguments made by the PAC and others that, in being depoliticised, the day has been rendered irrelevant and commemorated as a ritual with little meaningful content. So what should a more meaningful agenda for Human Rights Day look like?

Based on the events of the last few weeks, here are four agenda points for the day.

One

Firstly, the political intelligence mandate of the SSA should be removed entirely during upcoming debates on a new intelligence policy and the SSA Bill. To its credit, Parliament did narrow this mandate somewhat during legislative amendments in 2011, but it clearly still remains overbroad in its everyday practice.

While it could be (and has been) argued that political contests could threaten national security if they turn ugly, it has become abundantly clear that the SSA will not interpret this expanded mandate impartially. It will inevitably lead to politically important but inconvenient figures such as Greenpeace leader Kumi Naidoo, Public Protector Thuli Madonsela and others being investigated, rather than those who really need investigating.

Two

Secondly, the SSA and the National Prosecuting Authority should do something about the real threats to national security, such as the xenophobic attacks and the growing number of political and whistleblower assassinations in the country.

It is a national disgrace, but an unsurprising one, that while the security cluster has committed itself to fast-tracking the investigations and prosecutions of those engaged in disruptive protests, the investigation into the burning to death of Mozambican Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave, and other victims of xenophobic attacks, have gone nowhere. This is in spite of the Sunday Times having claimed to have tracked down eyewitnesses to Nhamuave’s gruesome murder. The security cluster’s lack of seriousness in dealing with xenophobia conveys the message that human rights belong to South Africans and non-African foreigners only.

Three

Thirdly, the South African Police Service (Saps) must commit itself to substantial demilitarisation – which has been widely blamed for growing police violence against protestors – and not just its most superficial manifestations. In fact, the police are talking left and walking right on demilitarisation.

SAPS seems to see the problem as being an issue of organisational culture only, where the military ranking system has lulled the police into believing that they are a military by another name. The National Development Plan and the recently-released draft White Paper on the Police appear to share this view.

But, on a much more substantial level, there are other signs of the police actually remilitarising.

Military-police weapons transfers are a sure sign of police militarisation. In September 2014, the police announced to the Portfolio Committee on Police that they had a number of war toys on order, including the controversial Long Range Acoustic Devices (or “sound cannons”). These cannons – which emit sounds loud enough to disrupt balance, and even burst eardrums and cause deafness – are weapons designed for military use, having been deployed during the invasion of Iraq.

Tellingly, various US police departments bought these weapons during the “occupy” protests, but declined to use then against protests of mainly middle-class students. Yet when protests broke out in mainly black-working class areas after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, the police wheeled the sounds cannons out to quell the protests.

The proliferation of paramilitary units and their normalisation in ordinary policing is another indicator of police militarisation. In South Africa, the numbers have trebled over the past decade, and increasingly they are being used in public order policing. One of these units, the Tactical Response Team, stands accused of widespread human rights abuses across Mpumalanga, and all three paramilitary units were deployed to Marikana. It is a democratic imperative that the paramilitary units are removed from public order policing.

Yet, the police’s new operational instruction on public order policing and the draft White Paper remain silent on this all-important issue, suggesting that their deployment will continue. If this happens, then there are likely to be more protestor deaths.

Four

Fourthly, while public attention has been focussed on paramilitary policing, a new, controversial and equally authoritarian policing model has crept quietly into Saps, namely intelligence-led policing. According to the SAPS strategic plan for 2010–2014, intelligence-led policing is a key strategy for the Service, and the draft White Paper confirms this shift.

The Crime Intelligence Division of SAPS holds the key to this new policing strategy, so it is unsurprising that this Division has become so powerful (and controversial) in recent years as this strategy puts it at the centre of so much police work.

But these documents are silent on just how controversial this policing model has become elsewhere, especially in one of the countries of its birth, Britain. Intelligence-led policing gained currency after the 2001 terrorist attacks in the US. It involves policing decisions based on the assessment and management of risk, and relies heavily on paid informants and surveillance techniques.

Its advocates argue that intelligence work allows the police to be much more targeted with respect to when and how it deploys resources. On the other hand, other policing forms, such as saturation policing, are resource-intensive and potentially alienating as they involve visible displays of brute force.

The problem is that intelligence-led policing tends to rely on highly intrusive methods of gathering information, such as biometrics, data mining and body scanning. Generalised surveillance techniques erode public trust in the state. Often, this form of policing also relies on public-private partnerships with private security companies, leading to an even greater loss of accountability over the police.

Intelligence-led policing could be used to predict who is likely to engage in criminal behaviour, leading to the police relying on a practice that has, until recently, remained the stuff of science fiction movies, namely pre-crime policing. With this model, human rights abuses do not disappear; they merely become less visible.

Pre-crime policing involves identifying possible crime threats before the occur; because of its pre-emptory nature, it can be used to profile individuals on the basis of pre-defined characteristics, such as religion, leading to official stereotyping and discrimination. The police can harass those they profile with relative impunity, given the secretive and often unaccountable nature of intelligence work.

As the Transnational Institute’s Ben Hayes commented recently

[Britain] should be having a serious conversation about the way “intelligence-led policing” has undermined our national security and human rights… [leading] to an undercover culture that has perverted the pursuit of social and legal justice in this country. It won’t, because we’ll turn a blind eye to anything at the drop of the T-word [terrorism].

These four agenda points are unlikely to feature in the official speeches on Human Rights Day, which is why progressive civil society and movements need to ensure that they occupy a central place in the day’s commemorations. After all, ensuring that the conditions that gave rise to the Sharpeville massacre never arise again, is the most meaningful way of honouring the memories of the fallen.

This article was originally published by The South African Civil Society Information Service, a nonprofit news agency promoting social justice.

The Argus Report Read about it!

The Argus Report Read about it!