Updated

March 27, 2020 12:05:56

Last winter, Australia suffered a vicious flu season that killed 812 Australians.

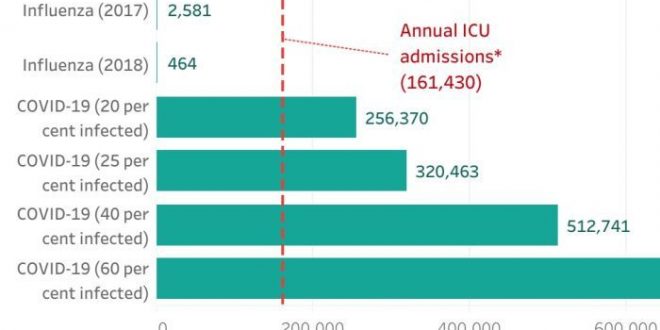

A bad flu season can land around 2,500 of us in ICU.

But if coronavirus infects 20 per cent of Australians as some state health departments are preparing for, about 100 times as many Australians will end up in intensive care.

Based on overseas experience, about 5 per cent of COVID-19 cases are “critical” and 14 per cent are “severe”. This means about 20 per cent of people with COVID-19 will require hospitalisation and 5 per cent will need intensive care, often involving artificial ventilation, where a machine helps you to breathe.

“Eighty per cent of those [infected] will get a very mild disease,” said Queensland chief health officer Jeanette Young.

“Then there’s 20 per cent who will do worse. And they are the numbers that we are preparing for in our hospital system.”

Here’s what those numbers could look like under various infection rates across the population. We don’t yet know what the infection rate will be, but NSW Health is preparing for the virus to infect 20 per cent of the state while Queensland Health is readying for 25 per cent this winter.

The virus may never reach this many Australians. But these are modest forecasts — for example, German chancellor Angela Merkel warned the virus could infect up to 70 per cent of Germans.

It’s also important to note that the admissions projected in this chart wouldn’t all happen at once, but surge periods are forecast where admissions threaten to outnumber beds.

As you can see, the flu hospitalisations are so small compared with COVID-19 projections that they barely appear on the chart. But Simon Judkins, former president of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, has previously told the ABC a bad flu season can push Australia’s hospitals to the brink.

So will they cope with this pandemic?

How many beds does Australia have?

If you’ve been in the bustling corridors of an Australian hospital, you’ll know there is rarely a spare bed.

Australia has just over 2,200 intensive care beds, with almost half of these in NSW.

That’s around 8.9 ICU beds per 100,000 people, which is better than New Zealand (5.1 beds) but worse than Italy (12.5), where COVID-19 has overwhelmed hospitals.

COVID-19 patients in ICU will need a bed for around 10 days, according to Imperial College modelling, which is a lot longer than the average time for other causes (just under four days). And those beds can mean the difference between surviving the disease and dying from it.

For the patients who will be hospitalised but won’t need intensive care, Australia has about 3.8 hospital beds for every 1,000 Australians, which is lower than the OECD average of 4.7. Japan and South Korea have more than triple Australia’s number of beds per capita.

Is that enough?

If NSW Health’s forecasts play out, 1.6 million people in NSW (20 per cent) will contract coronavirus, about 320,000 in the state will require hospitalisation and about 80,000 will need intensive care across the winter.

If Queensland Health’s predictions of a 25 per cent infection rate eventuate, more than 255,000 Queenslanders will require hospitalisation and almost 64,000 will require intensive care across several months.

If all the existing ICU beds were devoted to COVID-19 patients, there would be more patients than the amount of beds available by early April, assuming the virus kept spreading at its current rate.

If we couldn’t scale up to meet demand, Australia would see a situation like Italy, where doctors are forced to make heartbreaking decisions about who gets a ventilator and who is left to succumb to the virus.

And of course, the regular patients who need ICU care won’t disappear with coronavirus.

So what are we doing about it?

Hospitals are now racing to boost capacity as infections grow exponentially in Australia’s most populous states.

It costs about $4000 to $5000 a day to keep a patient in ICU, so scaling up is an expensive exercise. Most of that cost is staffing, as typically intensive care beds each have their own nurse monitoring around the clock.

Australia has around 2,300 beds equipped with ventilators but hospitals could boost this to 5,000 by adding in portable ventilators and operating-theatre beds.

Getting more ventilators in a pandemic isn’t simple, so Chief Scientist Alan Finkel is working with companies to try to produce another 5,000 here in Australia.

NSW Health says it is doubling the number of ICU beds and “ordering additional ventilators”.

But the Guardian reported a 10-week surge period predicted by NSW Health would put ICU departments between 115 and 330 per cent capacity and beds with ventilators at 145 to 300 per cent capacity, on top of baseline demands. It’s unclear if doubling beds would accommodate the upper end of those ranges.

Queensland Health told the ABC “Queensland’s hospitals are prepared to triple emergency department capacity and double intensive care unit capacity” and the state is acquiring 110 extra ventilators.

This would bring the number of ICU beds in Queensland to 1,006 for a projected 64,000 patients, although those patients would be spread out across the winter.

Victoria is adding 140 hospital beds for COVID-19 patients, including 12 intensive care beds and more ventilators.

The WA Government has ordered an extra 101 ventilators, and has access to another 50 in storage.

Australia sees about 160,000 admissions to ICU each year. If 20 per cent of Australia gets COVID-19, we’d see 256,000 ICU admissions across half as many months. Will the doubling of beds and potential quadrupling of ventilators be enough?

Australian Medical Association president Tony Bartone has previously warned ICU capacity will be a “significant issue”.

“We’ll never have enough to cope with a health emergency, a national health emergency, of the scale that potentially this could evolve to.”

But it’s not just about equipment.

Do we have enough nurses?

Each ICU bed is manned by one nurse, but in practice, that means the equivalent of five nurses working eight-hour shifts so the patient is monitored 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Doubling the number of beds means finding another 10,000 intensive care nurses if we wish to maintain a 1:1 patient to nurse ratio.

Intensive care specialists are concerned the federal pandemic plan could suggest ICU nurses will need to juggle multiple patients instead.

“The patients are really going to be quite critically ill and need incredibly intensive care — that’s what we’ve seen internationally,” Australian College of Critical Care Nurses president Alison Hodak told the Brisbane Times.

A US nurse running ventilators for COVID-19 patients described to ProPublica the challenges of working across multiple patients:

“I work 12-hour shifts. Right now, we are running about four times the number of ventilators than we normally have going. We have such a large volume of patients, but it’s really hard to find enough people to fill all the shifts.

“The caregiver-to-patient ratio has gone down, and you can’t spend as much time with each patient, you can’t adjust the vent settings as aggressively because you’re not going into the room as often. And we’re also trying to avoid going into the room as much as possible to reduce infection risk of staff and to conserve personal protective equipment.”

Currently, about half of the nurses in ICU have specialised post-graduate training in intensive care. Now, registered nurses from across hospitals are being trained up and ICU nurses who’ve moved on or retired are being called upon as reserves.

But the looming shortage of personal protective equipment like masks means even more nurses could be required as many will catch the virus themselves. In Spain, healthcare workers make up 12 per cent of the country’s coronavirus cases.

How do we take control?

While it’s up to health departments to shore up supplies, it’s our actions that will determine the infection rate.

If we were to reduce the infection rate across Australia from 25 per cent to 10, it would save about 190,000 ICU admissions.

Reducing pressure on our intensive care units will also bring the fatality rate down.

Modelling from the Imperial College London, which has informed UK policy, shows intervention to flatten the curve could reduce ICU demand by a whopping 69 per cent — that’s things like lockdowns and harsh physical distancing measures.

And as Megan Higgie and Andrew Kahn from James Cook University write, strong action to flatten the curve “buys us time”.

“Time to find a vaccine, time to increase ICU bed capacity and train staff, time to make more protective equipment like masks.”

You can help flatten the curve by staying home as much as possible, washing your hands regularly and keeping a physical distance from others.

Even if you are at minimal risk from COVID-19, it could determine whether there’s enough beds at your local hospital for the people who’ll need one.

Plus, you never know when you or someone you love might need a bed yourselves.

About the data:

- Influenza hospital admissions are estimations from the federal Department of Health obtained through their annual flu summaries for 2017 and 2018. Data for 2019 is not yet published.

- COVID-19 hospitalisations were projected with a 20 per cent hospitalisation rate based on the proportion of patients classified as severe and critical in China’s outbreak and indications from Australia’s chief medical officers. Demographic differences may influence the hospitalisation rate in Australia.

Topics:

First posted

March 27, 2020 06:04:20

The Argus Report Read about it!

The Argus Report Read about it!